Five Concsort

The five consort of Veronese's The Wedding at Cana

M. Lafarga (Author and Illustrator), P. Sanz (Author) & J. Camarero (Illustrator)

INDEX

Recommended Reading Guide: Annex I. Description of the successive Consort Transformation processes

The successive musical consorts that are observable through the analysis of the Veronese’s canvas The Wedding at Cana (1563) were transformed from one to another through a graphic-evolutionary process, both in terms of their nature and their instrumental configuration. The authors present here, and illustrate graphically, a documented model that accounts for these transformations. The purpose of this book is to offer the reader a map that serves as a guide throughout the investigations carried out.

Introduction

The work we present on this occasion is the synthesis and conclusion of a slow and laborious process that has occupied us for more than five years in the maniera of medieval copyist monks [1], when we began to isolate one by one all the visible elements in the central scene, occupied by the group of Venetian painter-musicians, both on the canvas and in the X-rays published by the Louvre Museum in the early 90s [2].

The process finally yielded the articulated detail of six consecutive linked formations, all of them instrumental except the original, a “sung” mass, typical of Venice, which consisted of a quartet of voices accompanied by the author on the harpsichord. All our designs have been drawn on the elements observed in the X-rays of the canvas, with the exception of a few licenses necessary to complete our argumentation. All of them have already been previously exhibited and published.

At the same time that we carry out this meticulous and detailed work, we also developed two other parallel strategies. The first one was the reasoned exposition of these formations (consort) through a series of conferences in higher educative centers of our country.

After this five years, it have been possible to disseminate in a free way these Lectures on the networks [3]. This series illustrates in a different way the content of our respective publications on the same topics [4].

The second strategy, equally laborious and conscientious, was the artistic recreation of these consort by Jorge Camarero, whose pictorial and digital expertise can be easily appreciated when leafing through these pages, and also in some of our previous works. In all cases, this task has been carried out following the patterns of the designs that we have obtained from the X-rays of the canvas.

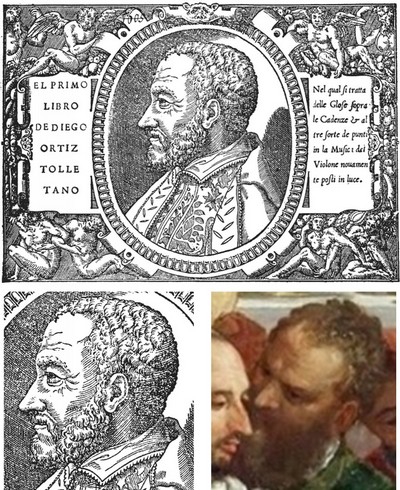

In reality, none of the five (perhaps six) formations that populated the canvas were completed in its whole. Except for the first one and original, the funeral mass that staged the lost Venetian citizen right of Giorgione [5], given that its two main designs ― the faces of both the author and the honored painter ― were perfectly completed and remained there almost until the completion of the canvas, with the arrival of Diego Ortiz to San Giorgio Maggiore.

Nor the current and definitive version that the Neapolitan maestro began to star in, taking into account the assortment of “dolci errori” that remain visible in the scene: the four phantom fingers peeking out from the cornettist ‘s back, the five elements, including Ortiz, which make up the mosaic outline of Veronese [6], the small page wedged under Benedetto Caliari ‘s armpit to offer the miraculous wine to the patron (displaced from the center of scene) [7], or the first Giorgione ‘s violin, embedded in Ortiz ‘s shoulder [8].

While lute consort was not [9], probably because the transition to the first violin band, leaving Titian ‘s bass lute unprinted: its design is not observed in the X-rays, while elements of Tintoretto ‘s soprano lute do appear. It is evident that Titian was also destined to support his own instrument, to give coherence to the characteristic formation that we know as “consort”.

It is possible, however, that the first violin band, which offers a consort with three soprano registers, was originally designed in this way, since its three respective silhouettes are indeed noticeable in the X-rays [10], necessarily belonging to the same canvas “moment”. This is a very rare formation during the Cinquecento [11].

In the current scene, however, there has been an undifferentiated remains in brown on the right side of Veronese, which was not finally hidden, but rather “disguised”. In addition to the fact that the shrunken face of the cherub on the author ‘s right shoulder, trying to hide his previous personification as Paolo II, is still perfectly visible in the X-rays.

This circumstance indicates that his old face as Paul II had already been roughly hidden, it means, that the transition to the next formation with violins had already begun. Attending these two reasons, we consider that this ensemble was not completely finished either, perhaps together with Tintoretto ‘s first right arm holding his bow.

The last of the consort that welcomed the honored and absent painter, the second violin band [12], was probably not completely finished either when Diego Ortiz finally arrived at San Giorgio Maggiore, since the face of the author ― who was already in his current position with his new tenor violin visible ― does not appear finished in the X-rays, conversely to his first embodiment as Paolo I harpsichordist. Just its outline can be seen, at this moment still adjacent to that of the good Giorgione.

This circumstance indicates that his old face as Paul II had already been roughly hidden, it means, that the transition to the next formation with violins had already begun. Attending these two reasons, we consider that this ensemble was not completely finished either, perhaps together with Tintoretto ‘s first right arm holding his bow.

The last of the consort that welcomed the honored and absent painter, the second violin band [12], was probably not completely finished either when Diego Ortiz finally arrived at San Giorgio Maggiore, since the face of the author ― who was already in his current position with his new tenor violin visible ― does not appear finished in the X-rays, conversely to his first embodiment as Paolo I harpsichordist. Just its outline can be seen, at this moment still adjacent to that of the good Giorgione.

In addition to the fact that the face of Paolo I still remained unhidden on the canvas, destined to be buried, like Giorgione, under what would be the second violin of the honored painter, in the only coherent position that the Veronese had left to erase his trace still present as a harpsichordist.

A simple description of the composition of the six consort is provided in Annex I, along with the Paolo Caliari ‘s role in each of them.

Thus, we close the cycle destined to the description of these musical formations by bringing to the eyes of the public, through the designs that we are postulating and the recreations that we are introducing, the vicissitudes suffered in the center of the scene by the brushes and the painters of Veronese, whose changing plans for this great canvas we have attempted to bring back to life.

We are reserving for the future the minute detail, “numbered” and “articulated”, of all the dolci errori that we have managed to identify on the canvas from its beginnings to its conclusion [13].

A simple description of the composition of the six consort is provided in Annex I, along with the Paolo Caliari ‘s role in each of them.

Thus, we close the cycle destined to the description of these musical formations by bringing to the eyes of the public, through the designs that we are postulating and the recreations that we are introducing, the vicissitudes suffered in the center of the scene by the brushes and the painters of Veronese, whose changing plans for this great canvas we have attempted to bring back to life.

We are reserving for the future the minute detail, “numbered” and “articulated”, of all the dolci errori that we have managed to identify on the canvas from its beginnings to its conclusion [13].

1. A well-travelled scaffold for a quiet refectory

Even though we had previously dedicated a monograph to every cconsort that populated, in an orderly succession, the great canvas of the Benedictine congregation of San Giorgio Maggiore [14], we have considered it useful, as well as beautiful, to introduce them here in a simpler, more elegant. In many senses, also more Palladian. The successive consort were transformed and rearranged through a graphic-evolutionary process: in terms of their nature at the moment the changes began in a constant way, and later in terms of their instrumental configuration [Annex I].

We cannot specify “when” the original funeral (sung) mass had to be dismantled, even with the harpsichord present. However, our working hypothesis is that this first ensemble remained unchanged for a long time, since both the face of Paolo harpsichordist [15] (and therefore also his instrument, which remains hidden), like that of Giorgione [16] in its same position for the first four consort, can be observed in the radiographs in a perfectly finished and unaltered way [17]. Therefore, it is possible to conjecture that these elements remained in this way till the end, it means, until the arrival of Ortiz [18].

The technical detail, both graphic and procedural, together with the rest of historical arguments and those derived from the deconstruction of the whole canvas as we are narrating here — the spatial conformation for musical ensembles of the central scene —, have been already explained in our previous work. Except for some specialized publications [19], it is freely accessible at our digital address www.theweddingatcana.org.

According to two romantic authors, a British antiquary [20] and a German painter [21], the large canvas which presided the refectory of San Giorgio Maggiore until the arrival of Napoleon ‘s troops, originated from a small modello that the Grimani family owned in their art gallery in Venice. At this time the patriarch of the family was the procurator of San Marco, Girolamo Grimani [22].

The abbot of the monastery, at this moment Girolamo Scroguerro [23], would have decided to reproduce it on a large scale in the dining room of his own congregation, presiding over the back wall of the refectory, the one that overlooked the lagoon, as a visual trompe l’ oeil raised two meters from the ground. The work was going to be gigantic, the largest of its time. It required a large scaffold for its completion, with several levels that remained static during the fifteen months of the commission — one would say that impassive taking in account all the events were going to happen.

Despite the deedless immutability of the matter that sustained the teams of painters, the activity that took place on the scaffold was instead a very dynamic enterprise.

The author was induced up to four times to alter or mutate the nature of the different consort, after the finished design (currently hidden) of the original ensemble: the funeral (sung) mass for his Venetian colleague Giorgione. In the last of them, even the honoree himself also disappeared definitely from the canvas.

Along the way, he faced some major problems. And some other minor, however equally curious. First of all, he had to dismantle the original consort and disperse the vocal quartet that was singing the mass: this forced the Caliari brothers to make drastic decisions already at the beginning, such as the lowering of the upper balcony together with the table of the guests, who previously overlapped the balustrade.

And, after converting again the consort that followed (the lutes one), he still had to move himself to the new table, in order to continue hiding previous designs.

At this moment, almost certainly some night, an unexpected and notorious event took place in the refectory. On his own shoulder, already advanced to his current location as Paolo III, perhaps a willful hand, but in any case a very inexperienced one, drew the “jibarized” portrait of his colleague Andrea Schiavone [24], in order to hide his own face as Paolo II.

The presence of this design on the canvas, which evidently does not belong to the Veronese ‘s bottega, is a curiosity that has still perplexed us ever since we first observed it. Undoubtedly, someone finally repaired the messed up, covering it with a portrait of a rejuvenated Schiavone as a cherub. Andrea was born the year Giorgione died, and he died in December, shortly after the painting was delivered.

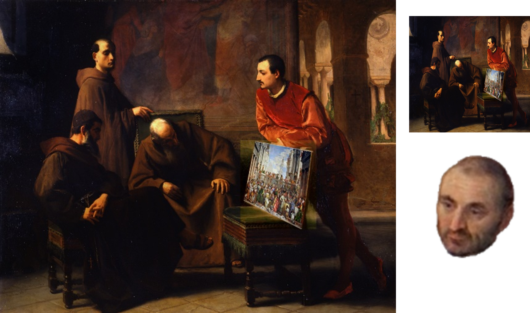

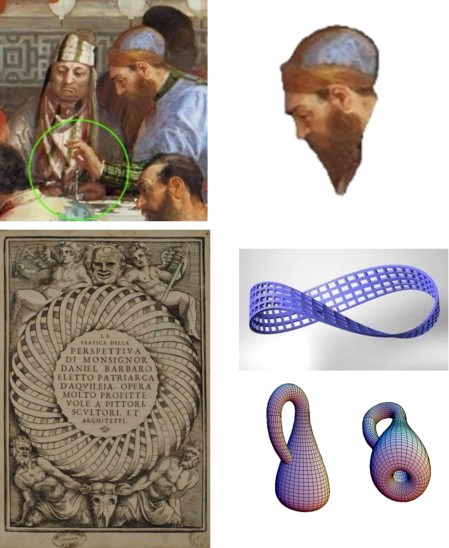

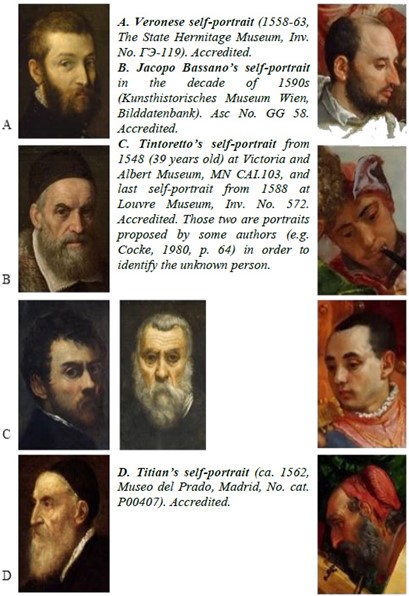

Figure 1

Paolo Caliari shows his model to Benedictine authorities of San Giorgio Magiore. Otto Gottfried Wichman. Berlin Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen, Nr.: W.S. 260. Depicted in Rome, 1856. Right: Girolamo Grimani and Girolamo Scroguerro, the civil and ecclesiastical patrons of the canvas, respectively. We have improved the modello, as a visual license.

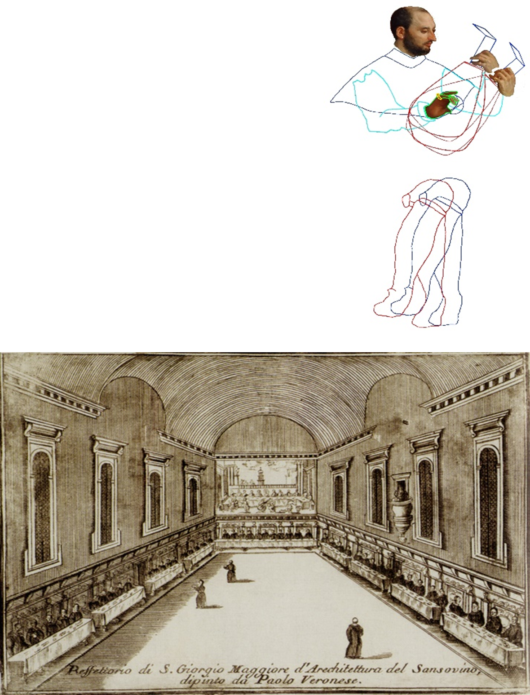

Figure 2

Paolo II “Frankenstein”, twice lutenist. © Manuel Lafarga. Below: the refectory of San Giorgio Maggiore. Engraving by Vincenzo María Coronelli, 1709.

2. The Consort 1: a funeral (sung) mass for Giorgione

The first formation that the Caliari brothers arranged with the authorities of the monastery was staging a Venetian funeral (sung) mass. This tradition, implanted more than one century ago, was the civic right of every citizen registered in the census of Venice. The least typical formation established by the city consisted of two human voices in charge of cantadori di morti, and, when separately financed, it consisted of a more professional vocal quartet accompanied in polyphonic mode by lutes or the harpsichord.

The lutes also occasionally took part in this rite, although already in the years of the canvas their sound (its “atmosphere”) was contemplated with an ancient (medieval) aura, which motivated, for example, that the Consort 2 mutated again into an ensemble more tuned with the current times.

Giorgio de Castelfranco, the most emblematic painter of the city at the beginning of the century, had died prematurely of the plague in the Venetian Lazzaretto, and was consequently buried in a common grave, deprived of his consecrated and undoubtedly deserved right.

So, the author of the painting, the civilian patron (Girolamo), and the Benedictine authorities (abbot Girolamo and prior Andrea [25]) finally agreed to award to Giorgione his pending funeral mass in the middle of their large canvas, which in addition illustrated a secular wedding.

The veracity of this assertion can be verified in the X-rays of the canvas, where it can be seen:

a) the perfectly finished designs of the author himself leaning over his instrument (the non visible harpsichord);

b) Giorgione ‘s in front of him, silent and impassive with his legendary lute; and

c) the remains of the vocal quartet that accompanied them.

In the original disegno, however, the civil patron Girolamo did not sit where we are seeing him today, at the inner end of the Benedictine table, but he was in the same position in the center of the scene, exactly on top of the current Titian, and peeking at the chords of his protégé Paolo [26].

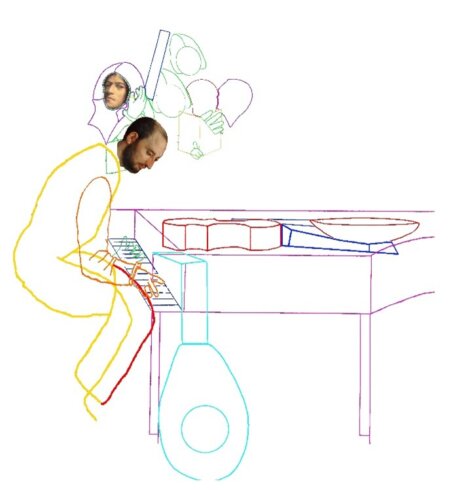

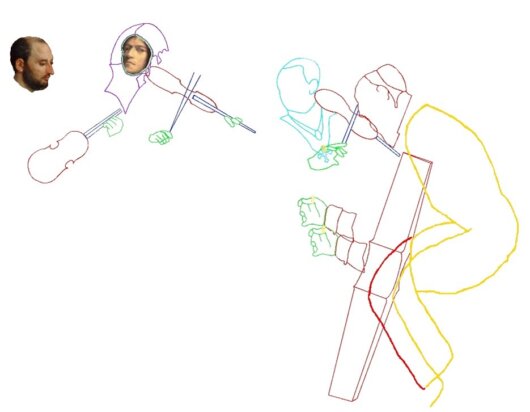

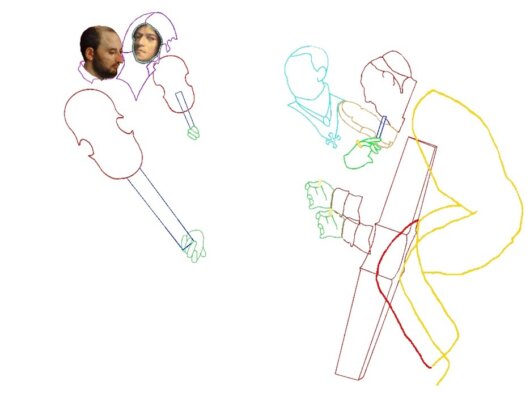

Figure 3

Figure 3. Silhouettes of the members of the original consort, showing the location of the harpsichordist ‘s true left hand. The standing bass lute is our license. © Manuel Lafarga.

Nor did Benedetto Caliari, the author ‘s brother, taste any wine in this first musical ensemble, since his extended left arm was painting the modello of the Grimanis in front of the monks’ table. The only wine served at this time was poured from a jug by a servant before Jesus Christ, the author of the miracle [27].

Two pulse instruments rested “mute” on top of the harpsichord case. One probably was a vihuela, attending to the verticals that define its eventual notches. The other one was clearly a flat oval lute behind the current Titian, however he (Titian) was in fact, during the life of the First Consort, the civil patron of the painting.

This second instrument was held by Benedetto with his extended right arm, while he was painting the small canvas for the Benedictines with his left, and its base was still visible in front of Girolamo. In this way, the author ‘s brother, the “geometer”, was the only guest who kept the link between the Arts explicit and visible, in this case Painting and Music.

It is virtually impossible that Holt and Wichmann known anything about the presence of this artifice, except if their source was a veridical one, since the modello did not surfaced until 1989, when radiographic analysis of the canvas was made because the canvas restoration [28].

We have added one last standing bass lute, resting on the Veronese keyboard box, whose right-angled headstock would exactly match the outline of the score over the current table, in front of Paolo playing viola da gamba. This design also allows to shape one of the two dogs at the feet of the painter-musicians.

After the dismantling of this first ensemble, the right arm of the original harpsichordist was reassigned to the marquis of Vasto, Alfonso de Ávalos [29], whose figure was probably generated at this moment: in fact, both he and his mirror figure on canvas [30] are seated outside the table [31].

Consequently, the original bride [32] had to disappear under a new portrait of Alfonso ‘s wife [33], once again complicating the legend that emanated from the canvas henceforth.

This is the only arm on the entire canvas that fits exactly in this same position for this precise function. While the silhouette of his own body leaning over the instrument (Paolo I) was inverted and reassigned to the new Titian, who came to occupy the empty seat that the patron Girolamo had left when he went to his corner with the monks. The “painter of princes” was dressed in his red mantle and remained in his new destination until the end. The consequences of this reconstruction process have already been detailed and analyzed elsewhere, and we will not insist here [34].

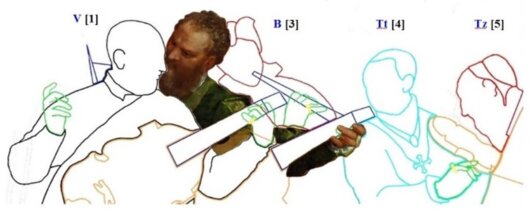

Figure 5

Artistic recreation of the First Consort. © Jorge Camarero.

Figure 4

Veronese ‘s silhouettes and designs for the First Consort, illustrating: a) the left arm of Benedetto Caliari painting the modello for the monks; b) the two pulse instruments on the harpsichord; c) the right arm of Paolo I that would be reassigned to Alfonso d’ Avalos after dismantling this original formation; d) the original ubication of Girolamo Grimani. © Manuel Lafarga.

3. The Intermediate Consort: Benedetto Caliari and the infinite recurrences

It is possible that there was an intermediate consort between the original mass and the first instrumental formation (lutes), because when Paolo ceased to play the harpsichord, he held the same lute for himself in two successive positions, and the first one prevented his brother from contemplating any glass. On the contrary, at this moment Benedetto was still painting with his left the small modello mentioned by Holt ‘s legend.

Lutes fulfilled the same polyphonic function as the harpsichord, and in fact also participated in these ceremonies. Since in the first position of the author ‘s lute his brother kept painting, Girolamo Grimani had to remain in his original position, now contemplating the chords of his protégé not to the harpsichord, but to the lute.

Figure 6 illustrates this arrangement, described by us like “intermediate”, and that we have already detailed and analyzed elsewhere [35]. The rotation of this same lute 15º clockwise, allowed us to establish the Second Consort (lutes), where Benedetto was already contemplating his miraculous wine after gave up his plastic work, Girolamo occupied his new seat thanks to the disappearance of the modello, and Titian was now the new “Girolamo”.

On the other hand, the new wine was now also offered to the displaced patron by a child fitted under Benedetto ‘s armpit, alike by a black page to the “new” bridegroom, the marquis with his recent new harpsichordist ‘s arm.

It is possible that the apparent existence of this ensemble could be just the result of contemplating all these elements, which were undoubtedly dynamic, in static (stable) environments such as the Renaissance consort. And consequently, that this intermediate consort could be just a “frozen” reflection of a series of successive and chained operations, which led to the new characteristic formation of the honored painter, that of lutes. The fold of Paolo ‘s current cloak, which crosses his chest from the shoulder, is exactly the upper contour of the case of his first lute.

In any case, we think that Benedetto ‘s small painting, already mentioned by Holt, introduces an artifice into the canvas consisting of an infinite recurrence, by including the entire scene within itself. So, it would be the first example of its kind in Western Art History.

Figure 6

Variation on the original funeral mass (Consort 1b). With his first lute, Paolo exercises the polyphonic function performed previously by the harpsichord, which is still present on the scene. Consequently, Girolamo Grimani can continue contemplating the scene, and Benedetto Caliari painting his little model for the monks. © M. Lafarga & J. Camarero.

Figure 7

Daniele Barbaro converses “visually” in The Wedding about geometry or architecture with the diner to his right. Center: cover of Daniele ‘s Treatise on Perspective. Below: Moebius strip and Klein bottle.

4. The Consort 2: Giorgione silent between lutes

From what was the first ensemble in the series of four sequential instrumental consort, that of lutes, all the performers remained in their respective positions until the end, except Giorgione, who finally disappeared in favor of Diego Ortiz.

The Second Consort still preserved the honorary atmosphere of the funeral rite, since lutes were also used for these purposes, playing the role of the harpsichord, it means, filling the polyphony of voices.

In addition, Giorgione had also been an accomplished lutenist, almost professional, beside to the fact that his “aura” was also nourished by this new skill in the city where all its painters were also musicians.

Paolo was already holding his second lute, as shown in Figure 9, thus allowing his brother Benedetto to incorporate his already discarded first arm to assess the cup with the miracle wine. Benedetto, who was perhaps left-handed (or ambidextrous) had to give up his small canvas when Girolamo Grimani went to sit in his current position.

Giorgione remained in the same position with the same attitude: silent and therefore somewhat absent from the active musical formation [39].

Perhaps this was an attempt by the Veronese to assert his sprezzatura¸ his ability to remain impassive to the events of the world, in this case the contemplation of his own funeral mass 50 years after his last mortal journey.

It is possible that Titian ‘s lute, the lowest register and therefore the biggest one, was not drawn because the need to move on to the next instrumental formation.

The cause in this case was probably the updating carried out by Venetian churches and confraternities in relation to the musical ensembles they maintained: the lutes had been gradually replaced by violin bands [40] .

Paolo ‘s lute illustrated in Figure 9 is his “second” lute, the one that corresponds to the Second Consort, when his first left arm is already owned by his brother with the miracle wine.

While his “second” left arm will finally be converted into his own to the tenor viola da gamba. In fact, we have reconstructed this “second” Paolo II by incorporating this same visible arm from the current canvas. His right arm instead (for his two lutes) is Tintoretto ‘s current one (and also that of his two previous soprano violins).

Figure 8

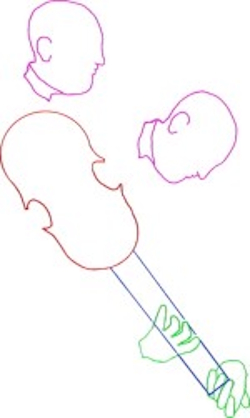

Silhouettes of the Second Consort (lutes) with Paolo ‘s first lute, which not correspond to this ensemble. © Manuel Lafarga.

Figure 9

Artistic recreation of the Second Consort. © Jorge Camarero.

5. The Consort 3: Giorgione violinist

Once again, Paolo transformed the musical ensemble into a first one violin consort, in order to please the monks of the congregation. It happened in tune both with the program of great reforms that they had undertaken in many of their monasteries, and with the new Venetian and Italian courtly fashions.Everyone remained in the same place, including the author, who was still his second incarnation (Paolo II), sitting one head backward than the current Paolo.

He adopted a small violin on his lap without playing it, while Tintoretto held the first of his three bowed-string soprano designs, including his ultimate viola. Titian took his bass register onwards.

Giorgione on the contrary, in spite he did not move from his original and primal position, became an active musician for the first time. He held a violin on his left shoulder that prevented the presence of the former monk, who sustained the vocal quartet score [41].

This violin was our guess during the first five years of our enterprise with the guests of San Giorgio Maggiore, since its outline is not appreciable in the X-rays of the canvas.

We had created this “first violin” after the outline of an almost contemporary instrument of Gasparo de Saló [42] (horizontally rotated from the viewer). And with this missing piece, however necessary, we continued our journey of deconstruction for all the ensembles stamped on the canvas until its conclusion.

In spite of all our efforts, we found it “alive” and still visible on the current canvas [43], exactly embedded in the shoulder, neck and hindhead, of the egregious viola da gamba player, Diego Ortiz. We looked so much under and inside the painting that we had stopped observing the real scene that the Veronese ‘s teams of painters finally revealed to us.

What is unusual about this formation is that it offers an instrumental arrangement of three soprano violins accompanied by a low register (Titian), a set that is not documented among the preserved sources, which mention the presence of only two.

6. The Consort 4: brass instruments among violins

Once again, everyone continued in their previous positions, except for Paolo, who now advanced one head towards the central table, perhaps to completely hide the trace of the old harpsichord ‘s keyboard. And perhaps for the same reason, he drew the neck of a new tenor violin above the keyboard, pointing towards the floor. His new left leg, bent forward, just helped him in this new endeavor.

However, the ancient silhouette of the original harpsichordist ‘s left hand seemed to rest on the neck of this new violin (Figure 12), and in the X-rays of the canvas could be seen an impossible cyborg violently twisted to his left.

This haunting chimera consists in the body of the current Paolo (Paolo III) with the harpsichordist ‘s head floating at his left side, and his legs crossed in an incoherent flexion. Alike this ancient hand, since even though it was assigned to the cyborg it could not be seen fully unfolded, as it appears on the radiographies.

This illusion has completely mistaked the scholars who have looked at these images until the publication of our works. The correct left hand for this violinist is shown in Figure 13 in green, at the end of the neck: Paolo III held his instrument by the headstock, but it was not active [44].

Titian kept his same instrument, and Tintoretto just moved his own from the “neck” to the “shoulder” position, and also his right arm and hand in tune with this small transformation.

On the other hand, the author ‘s advance to his new, third, and ultimate location (Paolo III) caused him some problems, derived in part from his haste, from the large number of modifications he had to undertake, and from the prompt delivery of the commission.

In consequence, he went for some perhaps hasty additions, which we have already discussed in detail elsewhere [45]: an undifferentiated brown area on his right side, the “aerial” nature of Andrea Schiavone over his own shoulder, and the inclusion of a Turkish trumpeter who paradoxically hides his face, in spite of to be among the most select cast of Venetian painters of the moment.

This new musician, especially his instrument, was also intended to disguise his former silhouette as Paolo II, who was first a lute player and later a violinist.

In this case, the true Paolo used the design of a U-shaped trumpet (Figure 17), an instrument for which no physical source has survived, except for three miniatures in two manuscripts around 1400 [46].

Likewise, the former monk holding the vocal score surfaced again, now playing a sacquebouche, the venerable ancestor of the trombones. Obviously, the hourglass could not be present at time [47]. At this moment, and thanks to these two brass designs added to the violin band, the identity of registers with the instrumental ensemble of San Marcos, in front of the island of San Giorgio, was almost total [48].

Figure 13

Silhouettes of the left hand of the harpsichord player (under the neck) and Paolo III violinist ‘s one (at the end of the neck). The leaned head is that of Paolo I harpsichordist.

Figure 14

Artistic recreation of the Fourth Consort, with brass instruments. © Jorge Camarero.

The second violin of Giorgione ― who should be active also in this second version of the violin band ― is again our conjecture, alike the vihuela resting on the harpsichord, Titian ‘s lute, or the silent bass lute leaned on the keyboard box. In a technical sense for the performance, we think that this was the only logical position for the author to finally hide his own original head, when he was leaned over the harpsichord (Paolo I), a still pending task [49].

It is likely, as we have just suggested, that this prevision never happened because the late arrival of Ortiz. Anycase, there is no doubt that it must happened even without the appearance of this circumstance, since Paolo I remained there ― finished and unaltered but “pending”, “floating”, as if dispossessed of a mortal body ― during all the transformations operated on the central scene, until the completion of the current consort.

In any case, Paolo I, and the hidden Giorgione ‘s lute case behind him, were both finally covered under Ortiz ‘s green shirt to the viola da gamba.

This was the instrumental formation that the Spanish musician contemplated upon his late arrival at the monastery, before the trombonist disappeared definitively following the same fate that had already suffered the servant who poured the original wine in front of Jesus Christ, and Eleonor of Austria, the first bride and also the emperor ‘s sister.

They were accompanied at this very moment by Giorgione himself, who in turn disappeared under the man who will eclipse his eternal fame for five centuries after his arrival, the maestro de capilla of the viceregal court of Naples, it means, of the Spanish crown.

7. The Consort 5: Diego Ortiz on bastard viola

In what was the last restructuring of the central consort, Tintoretto only transformed the body of his second violin (“on the shoulder”) into his current viola soprano.

While Titian just had to add a longitudinal band of varnish to increase the thickness of his instrument case, thus transforming the bass violin into its counterpart register for violas da gamba, and consequently trimming his companion ‘s small viola. Both facts can be easily appreciated in the current canvas and in Figure 15.

It is clear that Ortiz ‘s arrival at the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore must have been late, given in the first place the high number of mutations previously affecting the central scene.

And secondly, that these mutations did not begin in the first months of the canvas, taking into account, as we have already pointed out, that Veronese harpsichordist and his honored colleague were perfectly finished from the beginning.

In addition to the fact that Giorgione maintained his position and (practically) his posture all along, until he finally disappeared under the Neapolitan maestro.

Another obvious factor that points to this same circumstance is the fact that Veronese had never drawn violins in the face of Ortiz. However, earlier to the arrival of the Neapolitan maestro, Paolo had already printed two ensembles on the canvas with these instruments, which had a humbler origin than the violas da gamba family.

In the same sense, we think that the delay of the delivery, added to the problems carried on Veronese ‘s scaffold, precipitated a series of additions around the figure of the current Paolo, mainly in order to hide the trace of his previous silhouette as Paolo II.

We have already detailed this chained series of mutations elsewhere [50], so we will not insist here: a) the reconversion of his old left leg crossed over his right into the current stool that supports him; b) the undifferentiated brown area over his right side; and c) the appearance of the faceless Turk with his brass instrument.

We think that these three pentimenti were already there when Ortiz arrived, forming part of the Fourth Consort. While the addition of Ortiz and the cornettist to his left, helped Paolo to complete this “mosaic” around he himself and to hide Giorgione definitively, leading to completion of the current design.

Otherwise, we have previously documented that the register played by the maestro corresponds to the design of a “bastard” viola da gamba [51], a virtuoso and melodic model with 7 strings [52], intermediate between tenor and bass, capable of executing diminution and harmonies (chords) crossing all other registers [53].

Thus, we can affirm:

a) that Diego Ortiz is indeed the instructor of the consort of amateur Venetian painters-musicians; andb) that his instrument (viola bastarda) is, in addition, the oldest surviving iconographic source.

We estimate that the Spanish maestro probably arrived to the island around the end of the summer of 1563. We are proposing alike that he did so accompanying an entourage of Neapolitan authorities addressing to the conclusion of the Council of Trent [54].

The canvas of The Wedding was delivered to its owners in San Giorgio Maggiore on October 6, 1563 with a delay of two weeks from the date stipulated in the contract, the feast of the Madonna of the previous month. The birth of the Virgin Mary is currently celebrated on September 8, since the Gregorian Calendar was applied with the edict of 1582. At the time of the commission, the Julian Calendar governed, and the date alluded to was September 21: so, the commission was delayed about two weeks on the specified date [55].

Figure 16

Conclusion of the Council of Trent, December 4, 1563, probably the 23rd Session in the Cathedral of S. Vigilio in Trento. Italian School, 16th century, previously attributed to Titian. Louvre/R.M.N./Art Resource, NY.

Figure 15

Silhouettes of the musicians of the Fifth Consort, showing Ortiz ‘s engagement. © Manuel Lafarga.

Figure 17

Reconstruction of the U-shaped trumpet held by the faceless Turk behind the Veronese. CSMC Salvador Seguí, Castellón de la Plana. © Vicente Campos & Luis Escribano.

Annex I. Description of the successive Consort Transformation processes

Consort 1 – Vocal.

- Original vocal consort (monks I and II, plus Tintoretto and Titian) with harpsichord (Veronese).

- Giorgione remains silent with his lute upright.

Consort 2 – Lutes.

- The harpsichord is transformed into a table, and the body of the Veronese is inverted and assigned to Titian, who has been moved, along with Tintoretto, to their current positions, thus dissolving the original vocal consort.

- They all play lutes: Paolo II (alto); Tintoretto (soprano); Titian (bass).

- Giorgione remains silent with his lute upright.

Consort 3 – Violins.

- The lutes are replaced by violins with Giorgione now active.

- Paolo II (soprano); Giorgione (soprano); Tintoretto (soprano); Titian (bass).

Consort 4 – Violins.

- Andrea Schiavone hides the face of Paolo II lutenist and violinist.

- The faceless character holding a “U” trumpet and the strange brown area on the author's right side complete the concealment process of Paolo II.

- The monk I reappears as a trombonist (bassetto).

- The musical ensemble corresponds exactly to that active in San Marcos in 1563.

- Paolo III (tenor); Giorgione (soprano); Tintoretto (soprano); Titian (bass).

Consort 5 (actual / current) – Violas da gamba

- The violins are replaced by violas da gamba and Diego Ortiz definitively hides Giorgione.

- Jacopo Bassano playing the cornetto hides and replaces the trombonist monk who no longer fits with the new violas.

- Paolo III (tenor); Ortiz (viola bastarda); Tintoretto (soprano); Titian (bass); Bassano (basetto).

- Consort 1a Vocal with harpsichord - Paolo I

- Consort 1b [Vocal with lute] - Paolo II

- Consort 2 Lutes - Paolo II

- Consort 3 Violins - Paolo II

- Consort 4 Violins - Paolo III

- Consort 5 Violas da gamba - Paolo III

III. CONSORT 1B. VOCAL WITH LUTE © Manuel Lafarga / Jorge Camarero

V. CONSORT 3. VIOLINS © Jorge Camarero

II. CONSORT 1A. VOCAL WITH HARPSICHORD © Jorge Camarero

IV. CONSORT 2. LUTES © Jorge Camarero

VI. CONSORT 4. VIOLINS, TRUMPETS AND SAKBUT © Jorge Camarero

VII. CONSORT 5. VIOLAS DA GAMBA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Barbaro, Daniele (1568). La pratica della perspettiva. Venice: Camillo e Rutilio Borgominieri.

- Cocke, Richard (2001). Paolo Veronese. Piety and Display in an Age of Religious Reform. Surrey: Ashgate Pub Co.

- Duffin, R.W. (2016). Backward bells and barrel bells: Some notes on the early history of loud instruments. In: “Instruments and their Music in the Middle Ages”, Timothy J. McGee (Ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Faillant-Dumas, Lola (1992). “La plus grande radiographie réalisée au Louvre”. In: Les noces de Cana de Véronèse: une oeuvre et sa restauration. J. Habert, N. Volle & M.A. Belcour (Eds.). Paris: Editions de la Reunion des Musées Nationaux, pp. 110-129.

- Fenlon, Ian (1989). “Venice: Theatre of the World”, Chap. 3 of The Renaissance: From the 1470s to the end of the 16th-century. Ian Fenlon (Ed.). Cambridge: The Macmillan Press, Ltd., pp. 102-132.

- Glixon, Jonathan (2003). Honoring God and the City. Music at the Venetian Confraternities 1260-1806, New York, Oxford University Press.

- Holt, Henry F. (1867). “The Marriage at Cana”, by Paul Veronese (Part I). The Gentleman ‘s magazine, Volume 223, London, November: pp. 594-607. ISBN 0-521-65129-8.

- Holt, Henry F. (1867). “The Marriage at Cana”, by Paul Veronese (Part II), The Gentleman ‘s magazine, Volume 223, London, December: pp. 736-748. ISBN 0-521-65129-8.

- Lafarga, Manuel, Cháfer, Teresa, Navalón, Natividad & Alejano, Javier (2018). El Veronés y Giorgione en concierto: Diego Ortiz en Venecia (edición bilingüe Il Veronese and Giorgione in concerto: Diego Ortiz in Venice), M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds. ISBN: 978-84-09-07020-6. www.theweddingatcana.org

- Lafarga, Manuel & Sanz, Penélope (2019a). Las Bodas de Caná: la historia olvidada de un cuadro famoso, (edición bilingüe The Paolo Caliari ‘s Wedding at Cana: The forgotten History of a famous canvas), M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds. ISBN: ISBN: 978-84-09-16255-0. www.theweddingatcana.org

- Lafarga, Manuel & Sanz, Penélope (2019b). “Veronese and Diego Ortiz at San Giorgio: Profane Painters and Musicians and Sacred Places”. Bilingual Edition: Spanish-English. Paper presented at Lucca ‘s Conference of Music Patronage in Italy from the 15th to the 18th-Century. Centro Studi International Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, 16-18th November 2019. https://youtu.be/em2Cikj6Pd8. / www.theweddingatcana.org

- Lafarga, Manuel, Alejano, Javier & Sanz, Penélope (2019a). “Diego Ortiz : Un maestro de capilla español en Las Bodas de Caná del Veronés”, Musica & Figura, Vol. 6, pp. 43-64.

- Lafarga, Manuel, Llimerà, Vicente & Sanz, Penélope (2019b). Diego Ortiz y Giorgione: Dos maestros superpuestos en Las Bodas de Caná del Veronés, Anuari ISEACV, pp. 203-209.

- Lafarga, Manuel, Sanz, Penélope & Camarero, Jorge (2021a). Giorgio de Castelfranco y el Veronés en Las Bodas de Caná (1563). El Segundo Consort. Laúdes. Cullera, M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds. ISBN: 978-84-09-31601-4.

- Lafarga, Manuel, Cháfer, Teresa, Sanz, Penélope & Alejano, Javier (2021b). “Diego Ortiz y Giorgione in concerto. Nuevos hallazgos en Las Bodas de Caná del Veronés, 1563”. Musica & Figura, Vol. 8, pp. 29-58, (ilustraciones: pp. 216-223).

- Lafarga, Manuel & Sanz, Penélope (2022). “Tintoretto y Alessandro Vittoria: Artistas y patronos en Las Bodas de Caná del Veronés (1563)” (edición bilingüe: Tintoretto and Alessandro Vittoria: Artists and patrons at Veronese ‘s Wedding at Cana (1563). Cullera, M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds. ISBN: 978-84-09-32870-3. www.theweddingatcana.org

- Lafarga, Manuel & Sanz, Penélope (2023). “Mile dolci errori”: Giorgio de Castelfranco y la leyenda de Las Bodas de Caná del Veronés (1563), Cullera, M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds. ISBN: 978-84-09-52877-6.

- Lafarga, Manuel, Sanz, Penélope & Camarero, Jorge (2024a). Una misa fúnebre para Giorgione en Las Bodas de Caná (1563) del Veronés. Más allá del consort original. Cullera, M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds., ISBN: 978-84-09-52878-3.

- Lafarga, Manuel & Sanz, Penélope (2024b). Giorgio de Castelfranco y los violines perdidos de Las Bodas de Caná del Veronés (1563). Tercer y Cuarto consort. Cullera, M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds., ISBN: ISBN: 978-84-09-62291-7.

- Lafarga, Manuel & Sanz, Penélope. Antón Mª Zanetti el Joven y Las Bodas de Caná del Veronés (1563): Dos bodas históricas para un banquete bíblico, Cullera, M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds., (en preparación).

- Lafarga, Manuel & Sanz, Penélope. Arquitectos y escultores en Las Bodas de Caná (1563) de Paolo Caliari el Veronés. Cullera, M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds. (en preparación).

- Lafarga, Manuel & Sanz, Penélope. Benedetto Guidi: “Mille dolci errori” en el mecano del Veronés, Cullera, M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds., (en preparación).

- Lafarga, Manuel & Sanz, Penélope. Quién es quién en Las Bodas de Caná (1563) de Paolo Caliari el Veronés (edición bilingüe; Who is who in Paolo Caliari Veronese ‘s The Wedding at Cana, 1563). Cullera, M. Lafarga & P. Sanz eds. (en preparación).

- Martin, Thomas (1991). Grimani patronage in S. Giuseppe di Castello: Veronese, Vittoria and Smeraldi, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 133, No. 1065 (Dec), pp. 825-833.

- Morton, Joëlle (2014). “Redefining the Viola Bastarda: a Most Spurious Subject”, Viola da Gamba Society Journal, Vol. 8, pp. 1-64.

- Paras, Jason (1986). The music for viola bastarda, George Houle and Glenna Houle eds., Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

- Randel, Dan (1997). Diccionario Harvard de Música, D. Randel ed., Madrid, Alianza Editorial.

This material may be copied, distributed, displayed, and performed only verbatim copies of the work and only for non-commercial purposes. Are not allowed derivative works nor remixes based on it. You must give the authors and license holders the credits (attribution) in the manner specified by these.

Created under Creative Commons License:

Attibution – NonCommercial – NoDerivatives

(C) Manuel Lafarga Marqués, Penélope Sanz González & Jorge Camarero Manzanero